The Congress Party’s recent social media advertisement related to the Bihar elections shows a buffalo getting on a motorcycle and driving off, with the caption, “A buffalo can ride off on a motorbike, but the BJP cannot come to power in Bihar on its own.” Many non-Biharis seem to think that Bihar is a ‘Bharatiya Janata Party state’, lumping it together with the Hindi-speaking so-called ‘cow belt’ states. But in fact, the BJP has never formed a government in Bihar on its own, and has not even been the party with the largest share of seats in the legislative assembly, even though it has elected high numbers of BJP candidates in the parliamentary elections. So, why does Bihar persist in remaining an unconquered frontier for the BJP?

Communal conflict has been the driving force of Indian politics for the past decade, and Bihar has not been immune to it. The last ten years have been punctuated by episodes of mob lynching as recently as in Chhapra. Like elsewhere in India, Bihar has seen the sorry spectacle of Hindutva crowds attacking Muslim homes and mosques in Sitamarhi in 2023. Earlier in July, it was reported by far-right Hindutva social media accounts that a Mahavir Mandir in Katihar was attacked by ‘Islamist mobs’. Unlike in many other parts of the country, where the police has confirmed Hindutva narratives and joined in assaulting Muslims and filing weak cases against them, such stories rarely come out of Bihar. In fact, state officials are quick to say that in many such cases, “there is no communal angle” to the violence, which may or may not be true, but serves to scotch the communal narrative to Hindutva groups and thus the often lethal consequences such narratives lead to.

This is not to say that prejudice does not substitute for law in Bihar, as elsewhere in India, or that Bihar should be proud of its record on the rule of law. Far from it. But it may be that it is another kind of prejudice. Caste-based violence and even lynchings are reported from time to time, and only this month in Purnia a family of five was burnt to death after the women of the family were accused of ‘witchcraft’.

However, some of the sharpest weapons for perpetual communal antagonism used in other parts of India have not found traction in Bihar so far. True, we have our homegrown rabid preachers such as ‘Sherni’ Khushbu Pandey, who have a niche following, but no mass hate speech specialists such as T. Raja Singh or Narsinghanand stalk the land, stoking fear and exhorting violence or issuing threats of boycotts and evictions. Unlike Assam, Uttar Pradesh (UP) or Uttarakhand, the head of the government does not use virulent hate speech towards Muslims to shore up his popularity. As the party in the coalition government, BJP’s state leadership does not have the space, as in Maharashtra when it was in the Opposition, to ramp up conspiracy theories and hate-speech for electoral gain. Nor does it have a carefully-crafted hate-figure such as Mamata Banerjee against whom to outrage and falsify facts as a means to consolidate or expand its vote share. In fact, since it is partnered with Nitish Kumar’s JD(U), which has a substantial base among Muslims, and whose leaders are frequently seen at celebrations of Muslim festivals, some of the choicest communal barbs uttered by top leaders that hook voters in other states are simply non-starters in Bihar.

Another weapon of blatant majoritarianism, the bulldozer, has played well for the BJP, most prominently in UP: who can forget the clip of a young, jobless voter there saying to the news cameras that he votes for “buldojer ka majaa”, not on economic issues. It is interesting, isn’t it, that when you have the BJP as the sole party in power, the bulldozer becomes the arm of majoritarian prejudice masquerading as justice: almost all the episodes one hears of are in non-BJP states. The two instances in which bulldozers have recently been used have been against a rape-accused in Muzaffarpur, and an anti-encroachment drive in Patna: no communal angle has been reported. The use of bulldozers to keep the communal pot boiling by hurting Muslims in flagrant violation of Supreme Court orders is not a part of Bihari politics.

Not having monuments around which a politics of hurt, hatred, demolition and reconstruction can be built has been lucky for Bihar. Who knows how, had there been ‘disputed’ sites and mass mobilisations to destroy them, Bihar would have withstood the storm unleashed by Advani’s rathyatra? In their absence, there are no calls for “Kashi-Mathura baaki hai’’ that relate to realities on Bihari ground, nor a reserve army of kar sevaks that acts as Hindutva’s ground troops, and no successful drives to recruit those radicalised by the mosque-reclamation movements in UP.

Bihar’s folk Hinduism has proven difficult for the Sangh’s Hindutva to totally take over, as it has in many other places.

This is not to say that Bihar is a communal heaven: no state in India is right now. But the self-confident visibility of Muslims in public places is striking if one comes from a BJP- ruled state, as also the relative absence of flags of the Vishwa Hindu Parishad, Bajrang Dal or groups that have been part of the violent polarisation machine. To my knowledge, there have been no campaigns, as in more cosmopolitan Delhi, or in UP and Uttarakhand, to force Muslim shop owners to reveal their names. Nor can I recall campaigns to ban the sale or display of meat on certain days of the week or on certain Hindu festivals, as in Gurgaon, even though Biharis are second to none in keeping their vrats and vegetarian days. The ‘jhatka vs halal’ campaigns of the Sangh Parivar have few takers: Biharis know, as connoisseurs of fine mutton, that the best meat is halal, and line up in the hundreds in the well-known meat shops on Boring Canal Road, Bhattacharjee Road and Machhuatoli. The venomous food politics, so electorally productive for the BJP elsewhere in the Hindi belt, has just not found fertile ground here.

What this means is that the sharp and violent separation by religion has not materialised in Bihar. I recall scenes of a feudal conviviality during my childhood visits to my village of Itmadpur Sultan in Vashaili district, and of my grandfather, sitting at the end of the day with those who farmed his land, sharing hukka with his Muslim bataidaar friend Meer Hasan Mian—once of a noble family—both sitting on chairs, while those of the subordinated castes and poorer Muslim sharecroppers smoking their own hukka seated on the ground. Does that conviviality, not so grand as to be called ‘Ganga-Jamuna tehzeeb’, which sounds like an elite compact, still endure? Some years ago, I visited Hajipur’s sufi site, Mamu-Bhanje ka Tila. It was a ruin in my childhood, but now looked fully refurbished and thriving. The man in charge explained this was due to remittances from the Gulf, but that it was constructed by a Hindu king based in Nepal who saw the uncle-nephew, followers of Chishti Silsila, in a dream. “Dekhiye, hamare yahan sabse jaada Hindu ladies aati hain, bachcha theek se ho jaye uska mannat maangne ke liye,” gesturing towards sindoor-laden young women, though there were many in hijab as well. “Magar aaj kal sankat me hai dargah,” he said. Naively, I spoke sympathetically about the spread of Hindutva and the threat to Muslim sites. “Nahin sir, ek Muslim ne hi kes kiya hua hai,” he replied. The designs to take over the dargah had no communal angle.

Bihar’s folk Hinduism has proven difficult for the Sangh’s Hindutva to totally take over, as it has in many other places. Our kanwar destination, Deoghar, does not find police officers seated in helicopters showering rose petals on kanwariyas while they create communal mayhem as they do in UP: in fact, our kanwariyas do not seem so hell-bent on such public disorder. We worship the sun, rivers, trees, in addition of course to the other deities. The current Sangh push to project Bageshwar Baba Dhiren Shastri, asking directly for Hindu Rashtra, or Narendra Modi’s promise of a bhavya Janaki Temple in Sitamarhi are measures to fold Bihar’s diverse folk Hinduism into a grander narrative that binds religion to the Sangh’s muscular and exclusive nationalism, a project that remains incomplete in Bihar.

Bihar does not have the gaurakshak vigilante groups one often hears about from the BJP belt. Biharis love and respect cows like Hindus elsewhere in north India, but the absence of a Monu Manesar figure is another indication of Bihar having bucked the trend. A few years ago, I raised the issue of lethal cow vigilante violence against alleged ‘cattle traffickers’ in UP and Haryana with someone I know. He used to raise cows in rural Bihar but now worked as a driver-for-hire in Patna. He explained how expensive it was to raise cattle, and how the restrictions on selling them was denting his finances. What will you do now with your surplus cattle, I asked. “Kuchh nahin, raat me truck par daal kar door chhod aate hain.” I see Shankaracharya Swami Avimukteshwaranand has entered the Bihar electoral fray with his statement that ‘‘gau-rakshaks must contest every seat”, but he also seems to know this has no traction, saying ‘‘even if they get only one vote’’.

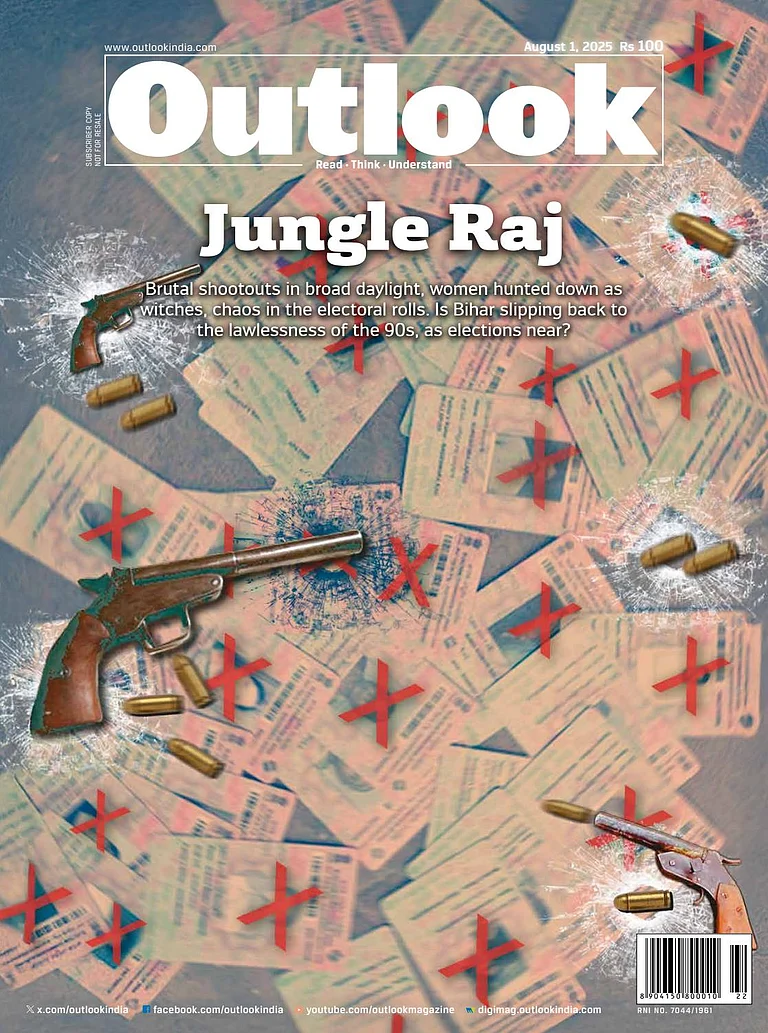

This is not to say that there is no polarisation in Bihar politics. Lalu Yadav and his family-led Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) is one such pole. For a large section of Bihar’s dominant and middle classes and castes, a government led by the RJD, even in coalition, is anathema because of an abiding fear of return to ‘jangalraj’, a time of lawlessness specific to Lalu’s rule and not applicable to any other time. The extended crime wave of the period, when the affluent classes did not dare leave home after dark, markets and shops downed their shutters early, party goons had a free run of the state capital, high-profile murders and rapes went unpunished, and the power of the ‘saalas’—Rabdi Devi’s notorious brothers—ran parallel to and above that of the state, is still invoked by those who ‘cannot bring themselves’ to vote for the RJD, however deep their disappointment in the NDA. But the ‘anyone but Lalu’ crowd misses the reason for Lalu’s popularity.

I recall a Patna University professor in my mohalla who routinely abused and sometimes even laid hands on rickshaw-pullers who asked for a higher fare than he wanted to pay being physically and verbally assaulted by one rickshaw-walla who, in between ma-behen gaalis, said “Ab Lalu aa gaya hai, aap haath nahin utha sakte hain.” Or my aunt who found it offensive that outside our village home “they are listening to their radio so loudly when previously they didn’t even light their lamps till the lamps in our homes went out.” Domestic workers, long used to taking orders, began to assert themselves on payment for sick days (naaga), and their wages increased. These were felt as major changes coming after centuries of caste oppression leading to the 1980s, a decade of violence against the subordinated castes. The actions taken by Lalu against the entry of Advani’s rathyatra, and the fact that no major riots happened after Bhagalpur, is remembered by Muslims, among whom the RJD remains popular. These reversals in feudal and communal oppressions are still resonant among those who support the RJD, making it, even now, the leading single party in Bihar. But this does not mean that the BJP will necessarily lose. The alternative, the Tejaswi Yadav-led RJD is popular, but his links to the Lalu family, and his lack of school and college education, are often trotted out as reasons some cannot bring themselves to vote for him, despite the fact that he has raised important questions of mass unemployment, lack of industry and infrastructure in the state.

In many ways, the grinding stones on which the blades of communal polarisation are sharpened are not as consequential in Bihar as elsewhere. The lack of deities or disputed sites around which to build a politics of violent communal polarisation, the insulation from mandir politics by Lalu’s long rule, which also limited the rise and spread of Hindutva groups, and representation to Muslims in positions of state authority, all mark Bihar as different from the rest of the Hindi belt. Since controlling state power is so important to win power, the BJP’s lack of full control over such power sets limits on its chances of victory. Despite outbreaks of violence, there is still a limited conviviality between religious communities. Dominant castes, outbreaks of caste violence notwithstanding, have sullenly accepted that with all political parties wooing them electorally, their violent oppression of subordinated castes is politically a losing proposition.

For these reasons, the BJP has had to recalibrate its electoral strategy. Having opposed the caste census, which has popularity in Bihar and is one of the UPA’s key planks, the BJP took a U-turn and affirmed its support. Modi’s branding of the humble makhana as a ‘superfood’ that he himself consumes, and the announcement of a Makhana Board, is aimed at the Maithili belt and the castes there that are engaged in its cultivation. So then you have inevitable freebies, the announcement of the distribution of two lakh rupees per Below Poverty Line (BPL) family. At the time of writing, the BJP’s Brahmastra—the Election Commission of India’s ‘special intensive revision’, widely opposed as it may disenfranchise non-BJP voters—is in the Supreme Court. These are signs of a party that, despite the popularity of Brand Modi, is jittery of the chances of its success, and will rely on all available means to either win Bihar on its own, or to retain it for its coalition.

(Views expressed are personal)

In Jungle Raj, 해외카지노’s August 1 issue, we explored why the Bihar elections matter so much. Our reporters delved into the state’s caste equations, governance records, electoral controversies and national ambitions, along with taking a hard look at the law and order situation— all of which make the 2025 Bihar Assembly elections one of the most consequential state polls of this electoral cycle.