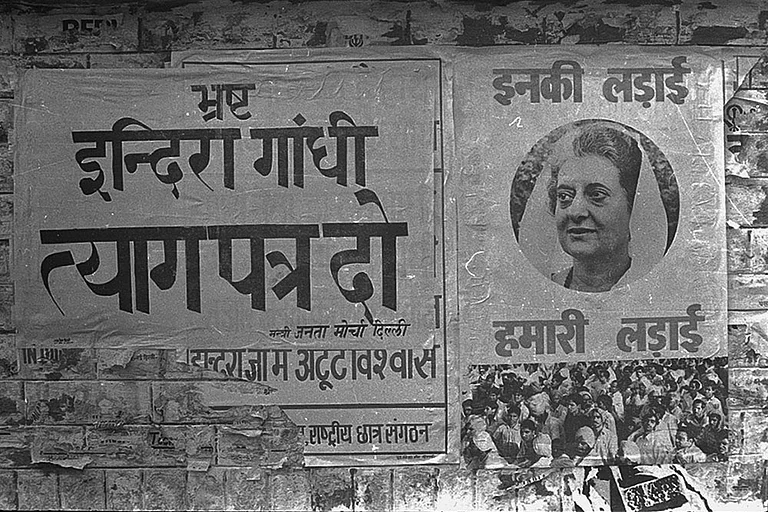

Mass sterilisation was the cornerstone of Sanjay Gandhi’s Five-Point Programme, introduced during the Emergency imposed on the country by his mother, the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. The programme included relatively banal efforts, such as for afforestation, dowry abolition, eradication of illiteracy and slum clearance. But it is the sterilisations pursued by him and his closest friends and supporters—and the government machinery—that damaged India’s family planning programme the most.

“Of Sanjay Gandhi’s five points… the other four were humdrum, unglamorous, hardly the stuff to build charismatic leadership credentials on. But family planning was. Here was a Herculean project, the solving of which, everyone acknowledged, was vital if the nation hoped to survive, let alone prosper,” the historian Ramachandra Guha wrote in India After Gandhi (2008).

The Emergency (June 1975 to March 1977) witnessed forced sterilisation drives that disproportionately targeted non-elite castes and poor communities. In 1976-77 alone, more than eight million people were sterilised, with most of this “accomplished” within six months, as the program was abruptly interrupted in January 1977 after Indira Gandhi announced a General Election.

Reports state that the sterilisation drives also disproportionately targeted the Muslims and Adivasis, exposing deep-seated biases within the institutional and governance framework. These communities were portrayed as the cause of their own poverty due to their (allegedly) higher birth rates, reinforcing stereotypes about identity and family size.

In a Muslim village in Haryana, men were rounded up by police for sterilisation, according to a report published in The Indian Express on 8 March 1977: “The villagers of Uttawar were shaken from their sleep by loudspeakers ordering the menfolk—all above 15—to assemble at the bus-stop on the main Nuh-Hodal road. When they emerged, they found their village surrounded by police. With the menfolk on the road, the police went into the village to see if anyone was hiding… As the villagers tell it, the men on the road were sorted into eligible cases… and they were taken from there to clinics to be sterilised.”

The BBC cites journalist Ajoy Bose and activist John Dayal’s book, For Reasons of State: Delhi Under Emergency (2018, Penguin Viking), “The real victims of forcible sterilisation and arbitrary demolitions were Dalits and Muslims at the bottom the social heap, most vulnerable to the depredations of the State.”

A paper by the Socio-Legal Information Centre (SLIC) records, “The weaker sections usually formed the focus of the raids. Persons belonging to the more prosperous sections were let off even though eminently eligible for sterilisation. Some, however, had to buy their ‘release’ by procuring substitute cases from the poorer classes.”

Reports suggested the “camp culture” of sterilisation was based on a target-based approach that disproportionately aimed at the marginalised. The approach posed a question, not of how many people existed but who enjoyed the privilege of having a future and who was denied choice, dignity and care. It drew inspiration from the notion that poverty and “overpopulation” reinforced each other. The logic was that poverty breeds overpopulation and overpopulation exacerbates poverty.

Aftershocks: Women’s Silent Burden

Years after Emergency, sterilisation campaigns shifted focus to women; female sterilisation becoming the largest mode of intervention at 36 per cent, while male sterilisation touched a mere 0.3 per cent, according to the National Family Health Survey for 2015-16.

In this way, almost the entire burden of family planning was placed on women, a logic devoid of empirical evidence. Sterilisation efforts must at least equally, if not more, focus on men due to lower risks, costs and the ease of the procedure for males.

According to “Mistreatment and Coercion: Unethical Sterilisation in India,” the SLIC report mentioned earlier, India carried out nearly forty lakh sterilisations during 2013–14. So, the trend continues. Between 2009 and 2012, over 700 deaths and 356 cases of complications were reported due to botched procedures.

These cases unmask the hasty approach of the government: unqualified staff, expired pain killers and non-disinfected tools unfit for surgery.

Another such incident, which caught media attention and led to a Public Interest Litigation (Devika Biswas v. Union of India) related to events that took place on the night of January 7, 2012. Just one doctor sterilised fifty-three women over two hours with the help of unqualified staff at a “camp” organised at Kaparfora Government Middle School in the Araria district of Bihar. There were no basic amenities, including running water or sterilising equipment.

Reports said women brought to the camp belonged to Below Poverty Line, Scheduled Caste and Other Backward Classes. These women were misled, manipulated or coerced. Women whose reproductive futures were decided for them, not by them.

“Neither the NGO nor the surgeon conducted pre-operative tests to determine suitability of the enlisted women for sterilisation,” said Devika Biswas, cited in the report. She belonged to Araria and was an eye-witness to the entire proceedings.

Going by the photos included in the report, post the operations, the women were left uncared for, and lay like cattle on straw as they bled profusely stripped of dignity while the government spread its population-control-for-betterment-of-all agenda.

Most Populous Country

In April 2023, India became the world’s most populous country, overtaking China, and its population has now crossed 1.4 billion. In the weeks that followed, media headlines rang alarm bells over dwindling resources, overcrowded cities and economic strain. This echoes narratives of the past that provoked “population control” policies, often advertised as a dire need.

For decades, “population control” policies were routinely framed as neutral tools aiming for development in a resource-scarce country. They were cloaked in the language of administrative jugglery and “over-population” bore the brunt these campaigns to preserve India’s allegedly scant resources. However, a closer look at what is conventionally masked as “development” debates reveals a more troubling picture. We are forced to wonder: whose burden is being counted and whose lives are being quietly discounted in the name of progress?

India’s population control policies have never been just about numbers, but rather they’ve always reeked of caste, gender and communal biases.

History of ‘Family Planning’ in India

In 1951, five years after independence, India became one of the first countries to launch a family planning programme, which sought to reduce the birth rate and “stabilise” population growth. At the time, India’s population was around 361 million, and R. A. Gopalaswami, a demographer and later Registrar General and ex-officio Census Commissioner, estimated that the population would grow by approximately 5,00,000 each year. By 1981, India would reach a population of 52 crore, but India surpassed that figure a decade earlier, in 1971.

In the early years after Independence, it was often presumed that the “population problem” would resolve itself through basic welfare plans. However, the population grew rapidly, until a massive dent was delivered by the unjustified mass sterilisations. Then pursued as a more permanent method of “controlling” population growth, it soon became evident that those in positions of power and control were actually viewing the Indian public not as a dividend to be maximised but a liability. Hopefully, those days never return to revisit our population “control” and family planning programmes.