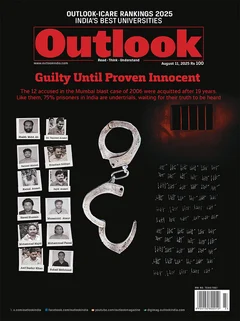

An July 11, 2006, a series of bomb blasts took place in the first-class coaches of multiple local trains in Mumbai. The incidents led to 187 people losing their lives, and since then justice has been prolonged and delayed for the aggrieved families. In the case, the 12 arrested and 15 absconding accused were tried by a sessions court, resulting in death sentences for many, and different terms of imprisonment for the rest. But on July 21, 2025, all the accused were acquitted by the Bombay High Court. The Government of Maharashtra has appealed against the decision in the Supreme Court, but for the moment, the High Court’s decision has been put on hold for the final judgement, leading to further delay in justice owed to the families of the victims. As of now, our experience indicates that the wait could take many years.

It’s not a hidden fact that the notion of the Indian criminal justice system is a product of the colonial system of tailoring the system as per their own Anglo-Saxon jurisprudence system. This system’s foundational basis is the belief that ‘a person shall be presumed innocent until proven guilty’, without leaving any room for doubt. In the Indian context, the belief would be right to the extent that it insulates common innocent citizens who could be trapped under false cases and punished by the corrupt police system. But Indian society does not meet their responsibilities of voluntarily presenting themselves before investigating officers. The Indian experience suggests that even an eyewitness would not come forward to testify. In most cases, the eyewitnesses testifying before the courts are pocket witnesses of the police, whom the courts consider reliable or unreliable as per their convenience.

Similarly, in the absence of any standard procedure, the materials presented as evidence by the police—after the recovery in connection with prosecution—become the basis for punishment or acquittal by the court as per their convenience. The lack of uniform procedure sows confusion in the minds of the common person regarding scientific evidence as well.

There is a lack of a mechanism to punish police personnel who commit atrocities against citizens through legal violence.

A detailed study of the Bombay High Court’s judgement draws attention to many anomalies plaguing the judicial system that have led to all the accused going scot-free even in heinous crime cases. A study of the judgement will help us understand how the government’s sloppiness, even on technical grounds, provides an edge to the accused. An interesting example of this is found in the identification parade of the accused. For identification parades, the Maharashtra government appoints a Special Executive Officer (SEO) for a fixed tenure; the process is a part of routine orders issued from time to time by office clerks.

One such officer was Shashikant Barve, a police inspector, who conducted the identification parade of some of the accused in jail. Now technically, when this parade happened, Barve’s tenure as SEO was over, and the government’s order on his appointment came days later. But this negligence by the clerks helped the accused in forming the opinion of the court, although the court mentioned that the identification parade is meant to assist the investigating officers.

A similar kind of confusion can also be seen in the witness identifying the accused after several months. Statements like ‘Why did the taxi driver not inform anyone immediately after the incidents?’ do not seem to be valid in the Indian context, as Indian experience shows that an average Indian would not like to be tied up in the hassle of police stations and courts, let alone be a witness, which is practised in extreme helplessness.

Human memory has been a topic of long debates in the courts. Now, the topic itself has now become an academic one. Citing the opinions of psychologists, the Indian Supreme Court, and the American Courts of Appeals, the Bombay High Court mentioned that human memory is never erased completely and can be recovered by some form of stimulus even after a long interval. On this premise, the incongruities in the statement given by the witness after a long interval can go in favour of both the prosecution and the defence—in this case, the court gave this benefit to the accused.

Our experience with such cases is that these would drag on for a long time, as it would be unfair to expect the witness to have the kind of memory to remember an accused whom they saw a long time ago for a very short duration. Often, during this long and tedious process, many of the witnesses, and sometimes even the accused, die—as it happened in this case. Recently, new laws were introduced in place of the old Indian Penal Code (IPC), the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), and the Indian Evidence Act. Union Home Minister Amit Shah claimed that with these new laws, the entire process—from the filing of an FIR to the Supreme Court verdict in any case—won’t take more than three years. It’s an unbelievable claim, especially for those who are aware of the ground realities of the Indian judicial process, but still, we can wait.

If the Supreme Court acquits the accused, then it would be perfectly natural to ask who will take responsibility for the 19 precious years that the accused spent in jail? Our experience suggests that every year a substantial number of innocent people become victims of police action, and when they are released, there’s no one to answer how the atrocities committed against them will be compensated. During my long period of service, I always felt the lack of any internal and spontaneous mechanism to punish police personnel who commit atrocities against citizens through legal violence. This is particularly true of communal clashes, when a large number of minorities are persecuted and never compensated even after their acquittal. Rarely is a police officer brought to justice for persecuting innocent citizens. Once the Supreme Court delivers the judgement, we will have to acknowledge and consider this as well. In such cases, the punishment should be awarded to not only low-grade officers, but also their supervisors.

Amidst all this discourse, who will answer the question of Ramesh Nair, who lost his daughter in the 2006 bomb blast? If the acquitted accused is innocent, then who is responsible for the death of his daughter on July 11, 2006?

(Views expressed are personal)

Vibhuti Narain Rai is a former IPS officer who retired as Director General of Police in Uttar Pradesh

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

해외카지노 Magazine’s next issue, “Guilty Until Proven Innocent”, looks at the 19 years lost of those who were in jail and those who thought justice was served, until it wasn’t. This article appears as 'Legal Lethargy' in the magazine